Words by Mac Woolley

My two friends and I had just moved into an old rowhouse in Oregon Hill with two floors, a mudroom, and a backyard. The walls were faded, and bugs could come in and out freely because of the cracks. We knew that things in the house were old and breaks were destined to happen. Sure enough, after a few weeks our dryer broke. The landlord said it would take a few weeks to get the part and have their repairman come and fix it.

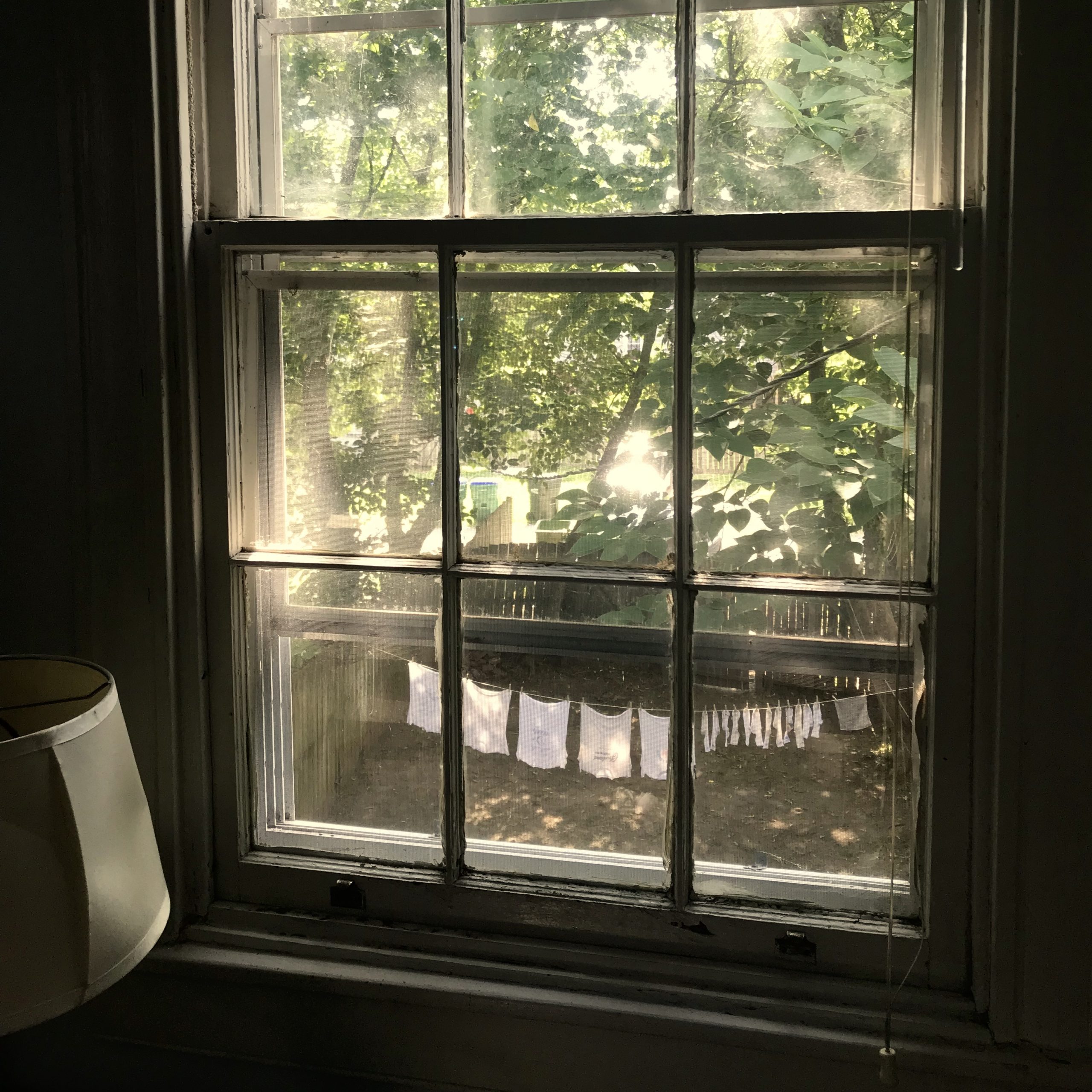

We considered going to the laundromat down the street. However, it was the middle of July, and while the summer heat was as unbearable as ever, it was the perfect weather for sun drying clothes. I remembered that I always liked the way clotheslines looked, and now; finally, I had an excuse to get one. All we needed was a wire and some clips. After a quick trip to the hardware store, I lazily tied one of those knot over knots with a ton of extra rope dangling down from each of the tall fences on either side of our yard. It was good enough.

When the time came, I lugged a full basket of clothes outside and started hanging them. At first, I wanted to get it done as fast as possible because I was so used to the speed of just tossing my clothes into the dryer. Then I started realizing how many little decisions I had to make about how I hung up my clothes. I strung the shirts up by the bottom, the pants by the belt loops, the socks by the toes, and the underwear by the waistband. I unconsciously kept things organized by size and type. I started on the left with my pants, then my shirts, then my socks, and then my underwear. I gave each garment their own clothespins, and spaced them about an inch apart. Then after a week of using it, I noticed how differently my roommates and I hung our clothes. There were variations in the organization of the clothes and the way they were hung. The whole process defamiliarized the weekly routine of laundry and after some time, the household chore became almost ritualistic and meditative. I looked forward to going into my backyard with all my clothes and really taking the time to do a task that usually would only last a moment.

My Clothesline

I even started enjoying the feel of sun-dried clothes. They were always a little stiff and crispy, but still warm if you took them down before dark. Even the way they folded was better because of the stiffness. And depending on the weather, the clothes would dry differently. Some days I would think to myself, “Wow. today would be a good day to do some laundry.”

I developed a new kind of attention to the environment. One day, I did laundry in the morning and went out to a park for the afternoon. Clouds started rolling in, and I could feel the rain coming and I immediately thought of my clothes out on the clothesline. I rushed home and barely got them off on time. As minimal as it may seem, I was more in-sync with the environment than I had been before.

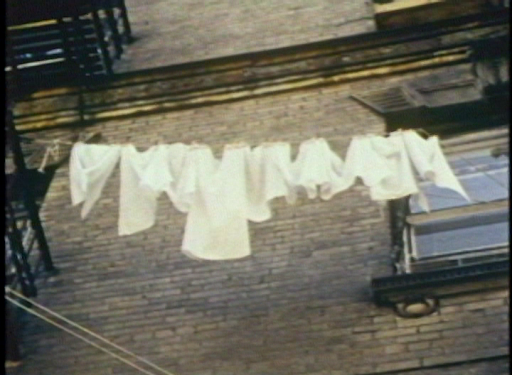

Not long after I started this practice, I came across a documentary from 1981 called Clotheslines by Roberta Cantow. It’s a 32-minute look at laundry from a sociological perspective told exclusively through the accounts of women in the 70s and 80s who used clotheslines in their daily lives. All of the accounts are played over found and shot footage with a dreamy sound design that meticulously mixes traditional instruments, seemingly random samples, and the voiceovers together.

The documentary focuses on the idea that laundry was an unnoticed form of folk art that oppressed and united women. Clotheslines were symbolic of all the unseen work of women. This grew even more apparent when Cantow was making the documentary because she said in an interview that men would ask why she was making a movie about such a trivial thing like laundry. The tradition and significance of laundry was totally overlooked.

Documentary Still

I think there are two quotes that speak to this tradition but also lay out pain that came with it. One woman says that the art of clotheslines was “a mastery that was not enjoyed.” Another woman says, “There was hatred but a strange inseparable tie.” Throughout the movie, you get sentiments from people who put incredible amounts of time and energy into their laundry. An unsuspecting amount of social significance was placed on it. Women in the film talk about how you could learn so much about someone through their laundry. You can tell how many people are in a family based on the number of clothes, how old people were, and what social statuses people had based on the types of clothes. You could even tell who was fooling around based on the type of underwear they had.

Documentary Still

In a way, it connected all the women in certain neighborhoods. The daily news was shared over the clotheslines. It was so entwined that one woman said that she could tell who was doing laundry based on the squeak of their clothesline. While the clotheslines were closely tied to the way of life in a community, they were also closely tied to the rigid delegation of housework at this period in history. A lot of the good and beauty in clotheslines really stemmed from subjugation. Women found a way to express themselves and connect in the way they did laundry. Cantow has said that the art of clotheslines was a result of “thwarted creativity invested in mundane tasking.” There is a moment in the documentary where a woman is talking about how much she put into her laundry and she begins to laugh at the end of her story. Cantow plays with the sound by overlaying and distorting her laugh with another recording of a woman crying. The merging of her laughter and painful tears is a perfect representation of the duality of the meaning of clotheslines in this era.

Clotheslines not only have symbolism in domestic life, but also in social classes and the environment. Some Homeowners Associations have even banned clotheslines because they are thought to be a signifier of poverty and decrease property value. Rules like this not only discourage the use of clean energy, but they perpetuate poverty by banning a great way to save money. They can also be seen as a form of gatekeeping against lower income families who want to avoid using dryers. There had to be a movement to regain the “right to dry” not long ago. Luckly, states have been overturning these restrictions in recent years.

It may seem like an insignificant part of our carbon footprint, but Sun drying clothes is a very impactful use of renewable energy. According to IGSenergy, dryers use up to eleven times more watts per hour than a washing machine making it one of the biggest energy holes in a house. Switching to a clothesline even for just a few months over the summer can help reduce our carbon footprint and save a good amount of money on the electric bill.

While clotheslines have a multitude of positive uses and meanings, it should be noted that there is a very complex history that lies beneath. I initially only thought of the aesthetic meditative pleasure of them with a slight consideration for the renewable energy aspect. Those are all very important, but like a lot of seemingly insignificant things in daily life, there is a greater conversation behind clotheslines.