Since her death, I think about my grandmother more than I ever did when she was just a phone call away. In fact, when she was just a phone call away, I never called. Our relationship is hard to explain. I myself have a hard time understanding just what exactly made me feel so close to her. We never talked much. The bond we shared felt like it existed more on a plane of shared energy rather than of dialogue. But because of this, I think so much about all the knowledge, the stories that have been lost. There are so many things I never brought up, never thought to ask, and now the chance to is lost; no one has the answers but her.

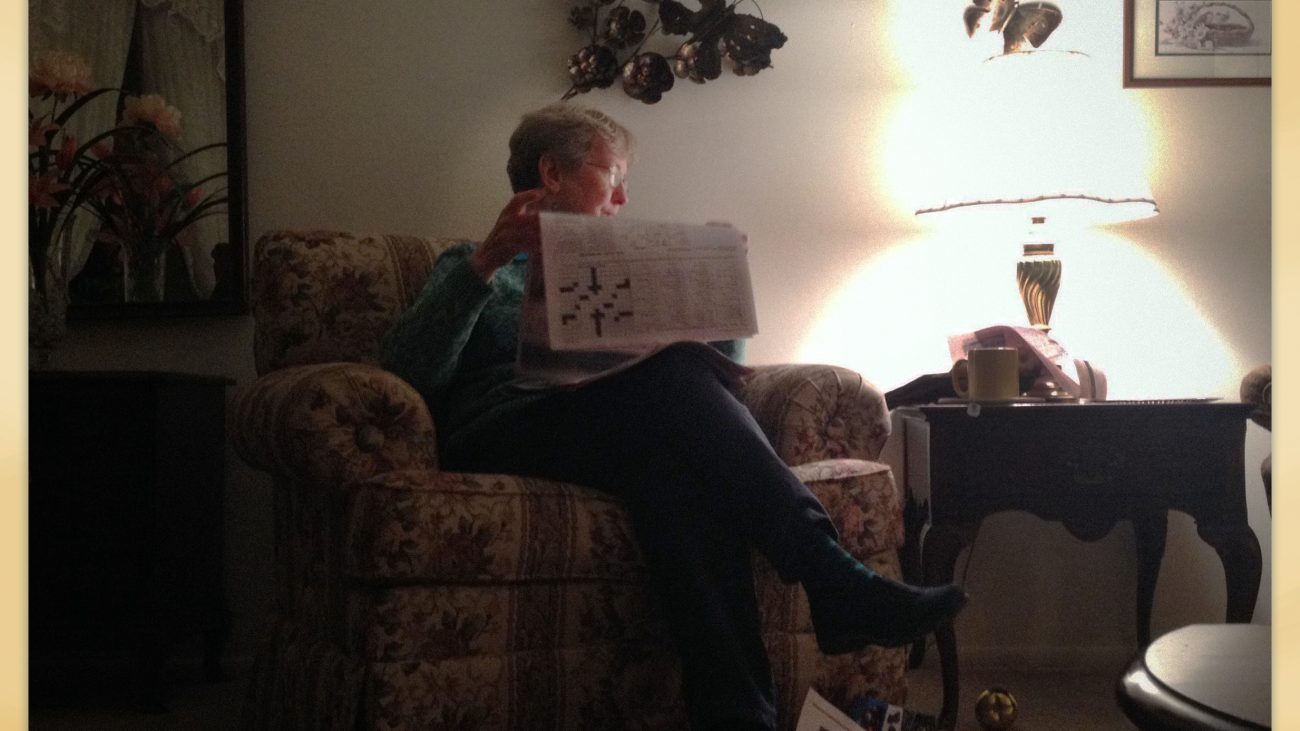

Growing up, my dad would drive us into Pennsylvania for monthly visits. Her home was like a time capsule. Striped wallpaper leftover from the seventies, olive green and mustard yellow furniture. Over the course of my life, I can count on one hand the number of changes her home underwent. Her ability to simply stay still, to resist unnecessary change, was enviable. She was solid, dependable, and predictable. Entering her home was one of my life’s greatest sources of comfort and stability. As a child, I didn’t understand the importance of stability, of constancy. I didn’t understand I had been suffering from its lack. Yet I knew finding the same red box of Legos on the same shelf in the same closet in the same red-carpeted basement with the same smell brought me a deep sense of calm. Of course, it couldn’t last forever, but I was incredulous of the idea that things could ever change when, up to that point, under that roof and between those walls, they essentially never had.

Along with my grandmother’s home, there was her cabin, Grey Haven. She bought it when I was about 10 years old. It was a tiny, blue-gray job with lights but no running water that my family would happily cram themselves into for the weekend. Without ever having to ask, I know that this must have been a dream come true for her. She and the family put in hours of work each time we visited, raking leaves, chopping wood, pumping and boiling water. Upon reaching a level of satisfaction with the work she’d accomplished, my grandmother would sit on the mildewed couch of the cabin’s front porch with the look of a cat in a sunbeam, warm and contented. There she’d stay as we all parted ways. To the animals of those woods, her stillness made her invisible, part of the scenery. It welcomed the natural world to resume itself in front of her, ignorant of her presence. I never asked her what she thought about while she sat. I was young at the time. Too young to think to ask. Young enough to take my time with her for granted.

While her thoughts on that porch will remain a mystery to me, she was always happy to share what she’d seen there since the last time we’d met. Chickadees and finches, titmice and robins, hummingbirds and woodpeckers, even racoons and black bears seemed oblivious to her quiet observation. I relished in the stories she told, always begging to know how she’d managed to see them all. Her response was simply: be still.

In the years leading up to her death, her mental health declined. She began to succumb to crippling anxiety. At gatherings with family, her tearful fits of laughter were replaced by quivering blue lips and a silence starkly dissimilar to the kind I witnessed in her at the cabin all those years ago. This silence was not meditative, not an invitation for wildlife to carry on around her as it was when she became part of the landscape on her porch, unnoticed by birds and bears alike. The silence of anxiety is a tongue cut out, not a mind at ease. It was almost unbearable to witness. Things had reached a breaking point. We all knew something needed to change.

The first thing to go was her cabin. The grandchildren had all grown and had busy lives of their own. The upkeep had become too much for being so seldom used. I was saddened by the news, but I had so much else on my mind I’d barely given it a second thought. But selling Grey Haven wasn’t enough to lighten her mental burden. As her condition declined, she made the difficult decision to leave her home and enter assisted living. In a few short months, we’d sorted her belongings, moved her into her new apartment, and her home was sold. The immaculately symmetrical vacuum lines of her living room, the type-written notes of all her grandchildren’s birthdays taped inside her kitchen cabinet, the bulletin board with her calendar surrounded by drawings my uncle had done 30 years prior, the red box of Legos on the same shelf of the same closet in the same basement with the same carpet and the same smell; it is all gone to me forever. It is unrecoverable. I will never go into that home again. She passed soon after.

I’ve struggled with anxiety all my life. Numerous phobias, fixations, and avoidances have plagued me throughout. After seeing such a strong and steadfast woman like my grandmother dissolve into an unrecognizable shell of the person I remember her as, I was almost happy I’d gotten it out of the way early. While my panic attacks have subsided as I’ve grown older, become more self-aware, and healed from various childhood traumas, depression and anxiety both still felt like they played larger roles than I would have liked them to in my life. I needed to do something to help steady myself. After my grandmother passed, my thoughts seemed to be constantly drawn back to her. I thought about her life before she had been overwhelmed by that enfeebling anxiety. I thought of her on the cabin porch. I thought of the birds. I thought of her words: be still.

But how to be still in a world like this? A world that insists upon movement, change, newness, upgrades; the next best thing in half the time, coming for us unceasingly. The encroachment of the digital world upon our daily lives, the encroachment of the world at large through tiny screens. Refugees’ malnourished faces in my bed, the Great Pacific Garbage Patch on the bus ride to work. Everything is urgent and everything is our fault. Fifty percent of the voices telling us to buy, buy, buy, and the latter fifty condemning us for doing it. But we each must find escape. To survive the spiraling and the guilt, the clicking and the sharing, the liking and tweeting, we must all find a way to be still.

My grandmother, her home and cabin may be gone from me on this plane, and none will ever be replaced, but the stillness, the stability, the constancy I lost when she passed, I’ve found again through birding. When I find I’ve lost track of the day, pursuing birds by sight and sound, becoming part of the natural world around me, allowing it to resume itself before my binoculared eyes, that’s when I feel closest to her. Before I lurch in excitement at the call of a long-sought specimen, I hear her in my mind: Now, just be still. And then I am. When I hear the birdsongs, the wind, her voice in my mind, I’m centered. The doom-scrolling, the advertisements, the infinite nature of ‘the feed’ we are engorged with, it all ends where the bird calls begin. It’s alright that her stories are lost to me, that I don’t know where she lived while at Columbia or where she acquired the trinkets we found in her jewelry box. The parts of life with the utmost importance are the bonds we form and the feelings they evoke within us. Bonds with friends, loved ones, lovers, the Earth. Bonds that allow us to be still.

Find your peace, whatever that may be. Find your peace and the birds will come.

—