Written by MiJin Cho

Pink Girl is a different breed; she’s unashamed of her eminent nudity. She holds her blonde hair back against the wind, leaning her neck forward to not interfere with the Sun’s penetrating rays. Her body is at peace: two legs looped casually together, her curves hugged by the wind, and her bathing gown—her second skin. Her skin is fair, a contrast to the Valencia custom in the late 19th century, in which children of working-class families come to the sea to bathe; and inevitably, tan under the Sun’s unyielding glare. Instead, Pink Girl looks directly at me, the painter, and the onlookers, putting on a soft smile as if to say, “what a warm day.”

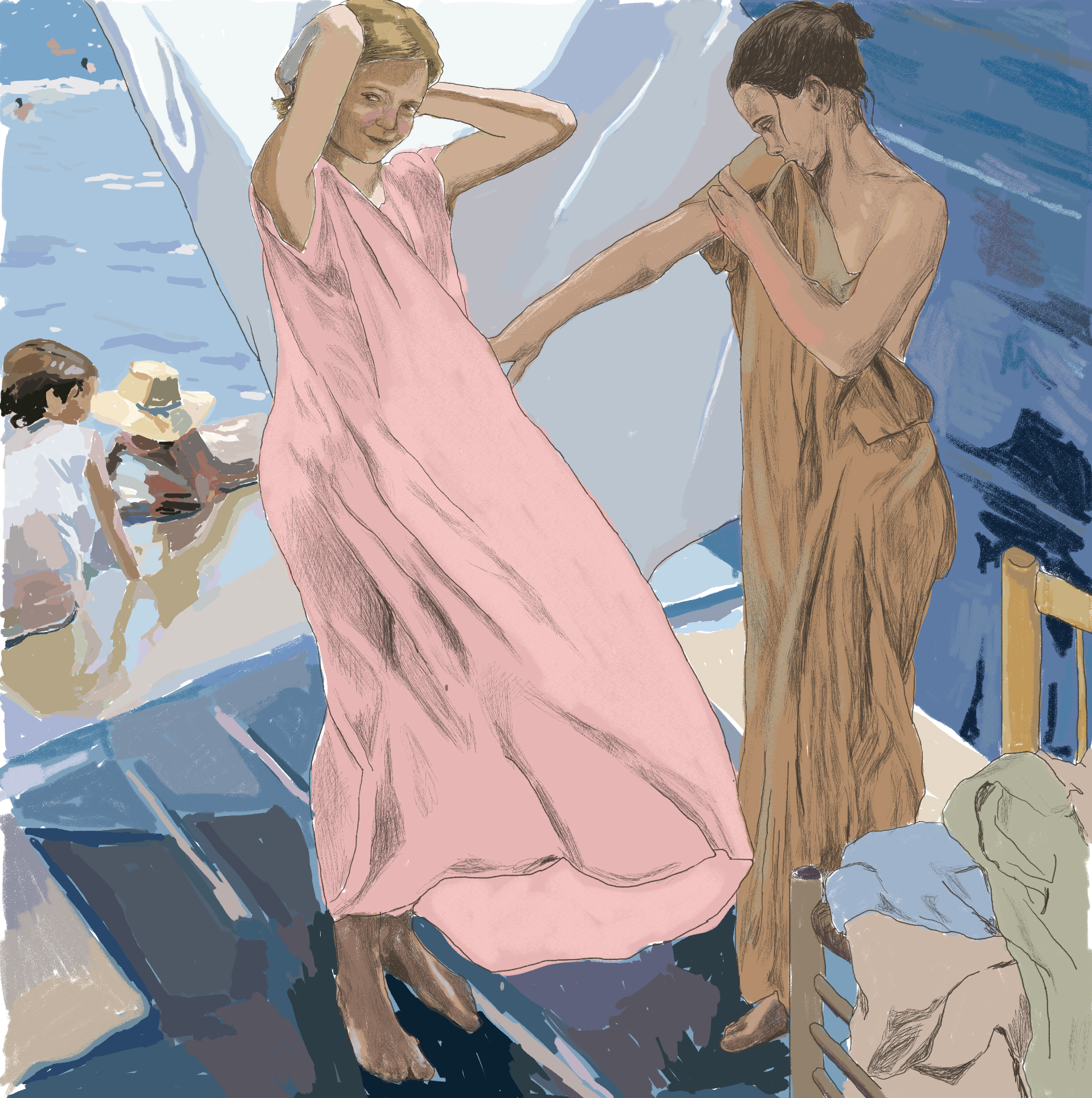

Sorolla’s 1909 impressionist painting, After Bathing, Valencia, recreates a scene of a probable photograph at one of Spain’s shores. The painting depicts two young girls, five or six years old, changing out of their pink and white bathing gowns behind a wooden wall, vaguely hidden from public view by a white drape. A brunette girl in white, standing closer to the wall, holds up the front of her gown with her mouth while releasing one sleeve from her right shoulder. She holds an aura of concentration, paying no attention to the two younger children fiddling in sand in the background. The girl in the pink gown, on the other hand, is situated closer to the shore than the wall, covering the other girl from unwanted exposure. She stands farther away from the wall’s shadow and closer to the light that infiltrates through the drape and the slits in the wooden wall. Sorolla puts Pink Girl at the core of the piece, narrating an intimate story of light, love, and the Spanish landscape.

Artist: Lowe Fehn

Caption: An illustration of Sorolla’s After Bathing, Valencia

Staring at the screen into Sorolla’s piece, I can feel the warmth. The dewy pastel contrasts in the seawater, wet sand, and Pink Girl’s bathing gown ignites a sensation of longing, of aching. I yearn to feel the sun’s embrace and the wind’s cradle as Pink Girl does—it’s a feeling I recall in my own nineteen years.

The pure and kind intimacy from Sorolla’s work resonates within me in the form of my mother’s kindred spirit on wintry nights. I’d hear the soft thuds of my mother’s traveling feet; moving from her bedroom and hesitating at my door. Innate, human loneliness travels alongside her at midnight. I’d let out a small sigh, a teasing sigh, and make a place for her in my queen-sized bed, where she promptly climbs in—ten steps away from the empty bedroom she left behind. I hold her hand, tight, and we’d share a small smile. We slowly drift off into conversation, placing pieces of our stories and wisdom into the compact space between a mother and a daughter.

On one such night, my mother told me a story of King David.

“King David,” my mom started. “When King David was old and weathered, he couldn’t keep warm even under the dozen covers of soft, animal material. Do you know what kept him warm?”

The question hung in the air. Eyes glazed with premeditated sleep, I rolled over to look at her and twerked my lips in soft curiosity.

“A young, plump girl they found in Abishag—a Shulammite,” my mother answered. “She kept him warm, without the intimacy of a lover. Just warmth.”

Mother gave me a teasing grin then, hinting me towards the mention of a “plump girl,” but I felt a pang of sadness. I felt an internal tug towards King David and his yearning of warmth; in a parallel sense, my mother, at the tender age of 50, had lost the ability to exuberate body warmth for long, wintry nights. I hugged her closer that night and hoped that my youth may keep her warm a little longer.

Artist: Lowe Fehn

Caption: An illustration of MiJin and her mother during the storytelling of King David

The harmonious coexistence of my mother and I, laying side-by-side on my bed at midnight, embodied me in safety and stability. Comforted by my mother’s presence, my night was hued in shades of pale yellow, beige, and white. The infiltrating moonlight, the linen covers, and the reflection of my mother’s freckles and skin tone. Those became the visuals of my own ease, my grounding, and my intimacy.

Such colors match the pigments of sand, the sun, and beach foam outlining Sorolla’s After Bathing, Valencia. While the rough skin of my mother’s hands and the moonlight continually guides my visual, Sorolla, in particular, utilizes the influence of Sun—a direct translation of a warm and endearing object—to convey his colors.

Named the “Master of Light” in a 2019 review by The Guardian, Sorolla did not always have the pull of the sun while growing up. Sorolla was orphaned at an early age and directly forged his path toward painting with the support of his aunt and uncle. Working as a lighting assistant to a local photographer, he found his calling in snapshot-like and well-lit paintings of the people and his native land, Spain. Under the sunlight of beach scenes and gardens, Sorolla’s affinity towards family, children, and smiles became a trademark in the early 20th century, most represented by his painting, My Wife and Daughters in the Garden. Sorolla articulates nuances of the light in his works, using the same blues and whites to represent shadows, fresh linen, and sunlight. With an anthology of hooks, dabs, and gliding swipes, he depicts sunbeams that infiltrate the deepest of shadows.

Sorolla’s determination and appreciation of the Sun drives him to embrace his subjects in the Sun and, eventually, his portraits of warmth. His passion parallels my own yearning to warm the frail body of my 5’2 mother as she takes her place next to me for slumber. Quietly, I run my hands through the white and grays strands of my mother’s head. Playing with the strands of hair, I find comfort in the way that Sorolla and I have each assembled our own personal portraits of emotionality and purity using the touch of a familiar presence. The unselfish nature of warmth draws people like Sorolla and I to cherish the fragility of moments when the sun, like the unconditional love of a mother, blares so shamelessly and unconditionally. When that fragile object of affection is broken, however, I could only imagine our hollow desperation for its pieces. Sarah Beth Childers brings this aspect of absence and vulnerability to light by contrasting humanity’s affinity for warmth with a poised narration of grief, longing, and internal entanglement with the death of a significant other.

Childers’ What Happens When You Drown is a creative nonfiction essay, written in a letter-style format composed to her deceased spouse about a change in her preference for swimming in the leisure pool at her university aquatic facility since his death. Her university has always held access to two main pools: fitness, an eleven-feet deep lane-based rectangle for active swimmers and professionals; and leisure, a four-feet deep freestyle space. Since the suicide of her husband, Childers states her affinity towards the slower, leisure pool with the water ball hoop, in which she can “put my feet down mid-lane when I start crying, and the warmth eases grief pains in my chest.” She finds solace as she coexists in the pool with the “professors emeriti [who] freestyle with saggy arms” and “soft-bellied mothers soak with swim-diapered infants.”

Artist: Lowe Fehn

Caption: An illustration of Childers’ What Happens When You Drown

Her essay, while filled with melancholy, presents distinct elements of warmth and coldness in grief; the leisure pool the former, and the fitness pool the latter. Her time in the leisure pool encapsulates an intimacy only possible with a body of water about “near the temperature of a womb.” She gets flashbacks to her husband’s “suntanned hands” wafting in a dirty West Virginia lake, his first movie night at another university pool, and his defiance of a lifeguard two years prior at Myrtle Beach. The warmth gives her time to consolidate past memories and recall a familiar yearning for engrained love and acceptance.

Childers then climbs out of the leisure pool, identifies her husband in the tile wall sign for ways swimmers may drown in the pool, and imagines his death in the sequence of images that follow on the sign. She drips water onto the pool deck with “goose-pimpled arms” and watches the scene unfold in her head until her swimsuit is nearly dry.

Childers’ story depicts her aching for warmth. She directs her piece with intimacy, informality, and deliberate uneasiness in the setting of gentle waters through memories of her husband. By characterizing the leisure pool, Childers presents an inherent power of warmth: the ability to conjure and remember memories of love and intimacy. Her appeal for thermic fluidity and remembrance is similar to the calling from Sorolla’s After Bathing, Valencia, in which the sunlight caresses Pink Girl, and my own heart’s tug towards my mother. An affinity toward light, warmth, and pieces of iridescent skies lies embedded in all three stories. Our own nature binds our mission toward self-assurance and emotional healing.