By Nilan Vaghjiani, contributing writer

Imagine, instead of going out on a late friday night to a local soiree, preparations are made to visit the nearest cemetery. This cemetery visit is not of sentimental nature and involves you, some hired henchmen, and shovels. In fact, this visit is a heist known as Body snatching: the secret disinterment of corpses from graveyards.

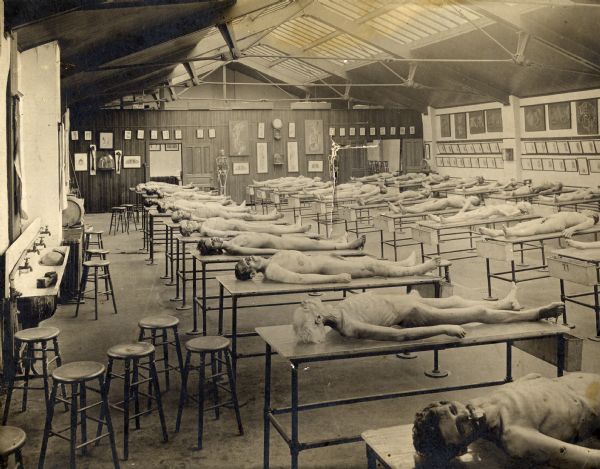

Body snatching originated as an attempt to train medical students in the 18th and 19th Century. Immediately, a major concern was the argument of preservation and respect for the deceased versus the social gain of knowledge. Medical students from this era would have argued that in order to have received a decent education and practice medicine on living patients correctly, a detailed knowledge of the human anatomy was necessary. However, at the time, laws only permitted the use of executed prisoners and unclaimed bodies. These laws created a shortage in samples; colleges needed their own way to make up the difference. Thus came the “resurrectionists.” These men would dig up the recently buried and carried them to medical colleges in the middle of the night.

More specifically, resurrectionists and body snatchers were a national sensation, popular with all the developing medical colleges, including the one in our backyard, the Medical College of Virginia (MCV). Dr. Micheal Sappol, senior historian in the History of Medicine Division of the National Library of Medicine, said “if you go through the history of any medical school in the year 1882, there will be some newspaper scandal – rumors or a court case or riot or something – relating to the acquisition of cadavers.”

Dr. Shawn Utsey professor at VCU Department of African American studies found the story of a local Richmonder, Chris Baker who was said to have been involved in the theft of hundreds of bodies from black cemeteries in the city. Originally born in 1860, he was employed by MCV as a resurrectionist. His original tasks included acquiring bodies both personally or by hire, recording deaths in the black community, and preserving bodies for dissection. In fact, Baker’s listed occupation in the 1890 census was “Anatomical man.”

Richmond was one of many populated cities booming in the cadaver business at this time. It is estimated that the number of bodies stolen range in the thousands. Dr. Todd Savitt, professor at East Carolina University, explained that the majority of cadavers were African American, not because they were being targeted, but were more vulnerable, (e.g. in municipal cemeteries that were open and unguarded), whereas their white counterparts were generally buried in churches or on their own property.

Even so, this risky business started taking a turn for the worse near the end of the 19th century. In 1882 protests aroused in Philadelphia against the robbing of six black corpses for Jefferson Medical College. Baker himself had trouble that same year, being indicted for one felony and two misdemeanors. With the coming of the 20th century, voluntary donations of bodies to science increased thus eliminating the need for body snatchers.

However, we still see the impact of Baker’s work today. In 1994, construction workers found a well at MCV with bones belonging to 26 individuals, some of which had surgical incisions on them, thought to have believed to be the cadavers acquired by Baker.