“To be a negro in this country and to be relatively conscious is to be at rage most of the time.” – James Baldwin.

Written by Camryn Smith

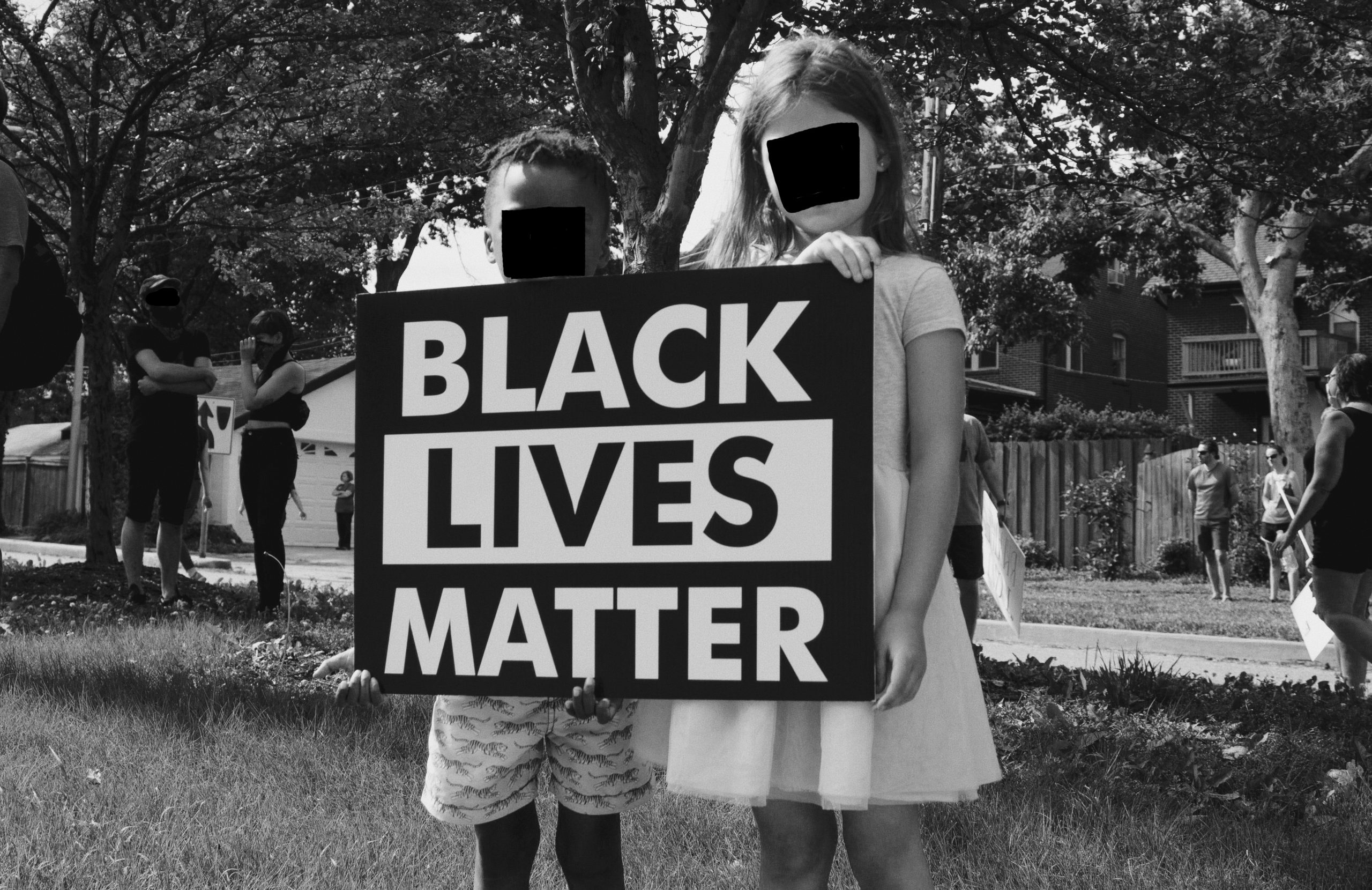

Photo courtesy of Adam Sherberg, note: obscured for safety of minors

The year I turned thirteen, I became radicalized. I was not radicalized in a literal sense, as I was too young and too naive to understand the power I wielded. However, the year I turned thirteen, my innocence was ripped from my grasp and I was left to nurse the fleshy open wounds of fury and fear. At thirteen years old, I learned it was naive to believe I had more time to remain unaware. I know now that a legacy of oppression in this country forces Black children to shed the dewy malleable skin of innocence and replace it with a hardened leathery shell. My parents grew weary with concern as I was plagued by bursts of rage at the slightest inconvenience. I did not know how to explain the feeling that permanently resided in the pit of my stomach, except that it could be likened to betrayal. When you’re young, adults inform you of the anatomy of consequence. By adhering to the established rules, you avoid consequences, by violating the rules, you welcome consequence inside. Justice is presented as not only attainable, but guaranteed. The year I turned thirteen I discovered the foundation through which my identity had been shaped, the hands of justice, and equitable distribution of consequences, were all a lie.

It was a few weeks after my thirteenth birthday. I was exhausted after track practice, and buzzing with excitement about the upcoming meet. I was a highly competitive child and eagerly boasted to my parents that my teammates and I were going to defend our undefeated title in the 4 by 1. For those unfamiliar with track, a 4 by 1 is a group race where 4 teammates compete together by each racing 100 meters. I stood in my parents’ room that evening as CNN played faintly in the background, discussing the dietary changes I needed to make to ultimately obtain the anchor position by the end of the season. The anchor is last and generally fastest competitor in the 4 by 1, and my main competition was a quick-footed eighth-grader who I was certain I could outrun. I don’t remember what my Mother replied, though, because, in the minutes that followed, I learned Trayvon Martin’s name for the first time.

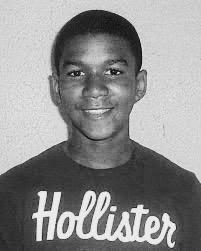

Trayvon Martin was murdered on February 26th, 2012 at the age of seventeen. As the story unfolded, I measured the ways he was like me. He was 65 meters from his front door, shorter than the length of the 4 by 1, my only concern minutes before. Trayvon Martin was running for survival, I was running to pass the time. Trayvon Martin died six hours before my thirteenth birthday. As my family and I celebrated my life, Trayvon Martin was begging for the preservation of his. It had not occurred to me that unarmed Black teenagers, walking home from the grocery store, died. CNN pundits flashed a picture of Trayvon Martin, smiling, in a bright red shirt. It was then the claws of betrayal first clenched their hands around my throat. When I saw Trayvon Martin for the first time, I saw the exact kind of boy I would have a crush on. Conversely, when George Zimmerman saw Trayvon Martin for the first time, he saw a threat. I learned, in that moment, that to be Black in America is an act of rebellion.

via Unknown Source

In the Summer of 2012, I compartmentalized my life into cardboard boxes marked for an affluent white suburb in St. Louis. I carried my packed bags as the Gateway Arch flickered into view. Ironically, the symbol of hope is representative of the trauma I was slated to endure. Racism lurks in the shadows of the black experience and is often disguised behind coded language and microaggressions. In St. Louis, the racism is blatant, unrelenting, and debilitating. I attended a predominately white school where my rage quietly festered and swelled each day. The students at my high school insisted on finding new and creative ways to break the black mind and spirit. In tandem, police officers across the country fought to break the black body.

In the Summer of 2013, George Zimmerman was acquitted of the murder of Trayvon Martin. Almost one year to the day of his acquittal, in 2014, Eric Garner, unarmed, was murdered in New York. He lay dying on his stomach, as he uttered his last words through a gargled gasped plea “I can’t breathe.” His murderer, Daniel Pantaleo, was not indicted for his murder. One month later, in August 2014, Michael Brown, unarmed, was shot and killed by Darren Wilson in the suburb of St. Louis, Ferguson. According to witness Dorian Johnson, Michael Brown had his hands up. Wilson was not indicted for his murder. A few months later, in November 2014, Tamir Rice, unarmed, was shot and killed by police officers at the tender age of twelve. Timothy Loehmann, despite being deemed too volatile for duty, was not indicted for his murder. A few months after that, in April 2015, Freddie Gray, unarmed, was murdered in Baltimore, Maryland. Six officers were charged, all were acquitted. Shortly after that, in July 2015, Sandra Bland, unarmed, was murdered after a traffic stop in Texas. Her death was ruled a suicide and, you guessed it, no officers were indicted for her murder.

In effect, The United States of America, the police force, and the judicial system confirmed what the history of this country had already proven; existing while Black is considered a radical act of defiance. The value of our lives became a national debate, as primarily white pundits, students, and elected officials gave a list of justifications for murder in response to the Black Lives Matter movement. The message sent to Black children was that the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness was not intended for us. How could it, at a time when our bodies were only considered three fifths human. Our parents hung their heads in grief, as their children came to understand what they already knew.

While in St. Louis, my family I briefly lived in a community of townhouses and condominiums as we searched for a permanent residence. We were located directly across a local grocery store brimming with tantalizing temptation. My sister and I were often denied sweet treats in favor of a healthy diet, and a grocery store in proximity opened a host of new possibilities. We made clandestine runs after school, as my Mother forbade us from going alone. On an unusually warm afternoon, we lingered outside in hopes of catching the sunlight dancing overhead. We relished in the feeling of freedom and being young, with hands sticky from the crystals of sour. We would learn that day that to be Black in America is to be under constant threat of siege. Suddenly, without warning, A car blocked our path. The seconds it took for the window to roll down felt like an eternity. It revealed a middle-aged white man, whose eyes were hardened from the evils in his heart I do not care to learn.

“What are you doing here?” He commanded. His birthright was the privilege of asking two young Black girls, alone, why they were playing in their own neighborhood. My rage boiled beneath my skin while slithering from the valleys of my stomach through my veins.

“We live here.” I volleyed the words against him, charged with defiance. My eyes quickly scanned an escape route, as the shadow of death loomed over our heads.

“No you don’t, I’ve never seen you before.” The arrogance of white privilege gives you the belief of ownership of the black experience.

“We live here.” We maintained. We remained, frozen, propelled by disbelief, and fear.

“Get out of here.” He replied before the screech of his tires pulled him away. We returned home, defeated by the realization that Trayvon Martin died for less. That night, I wept low, guttural sobs. I understood that day, and every day since, being Black means reconciling the proximity in which our existence lingers near death. I purged myself of grief that day, dried my tears, and surrendered to rage.

Three years have passed since I graduated high school and left the Gateway Arch in my rearview mirror. The roiling tides of America have bowed and broken since then, as Donald Trump became arguably the most divisive president of the modern era. A global pandemic has ravished the country and left 102,000 Americans dead. Black and Brown communities are disproportionately impacted by the virus, due to the systemic inequalities built into the fabric of this country. While Black and Brown people have the highest rates of essential workers, healthcare inequities severely decrease their access to life-saving treatment. In February, Ahmaud Arbery, unarmed, was slaughtered while jogging in Georgia. His murder didn’t gain traction until the video of his execution was released, sparking unwavering outrage. A few weeks later, Breonna Taylor, an essential worker, was shot and killed in her own bed while sleeping. Police officers had mistakenly raided her and her boyfriend’s home. In response, disoriented, her boyfriend fired back, unaware police officers had unlawfully entered his home. He was arrested and released 10 weeks later only after public outrage. Last Monday, Amy Cooper and Christian Cooper (unrelated) were the number one trending topic on Twitter. In a video released by his sister, Christian Cooper politely asked Amy Cooper to adhere to the rules of Central Park and leash her dog. In response, she phoned the police and feigned distress in order to vilify a Black man in a park. As a black person in America, you quickly understand the subtext of Amy Cooper’s actions. Amy Cooper was offended that a Black man would dare challenge the authority she was gifted as the birthright of being white in America. The manufactured histrionics depicted in the recording of the altercation, coupled with and the history of police brutality against Black men, leads to the conclusion that Amy Cooper was calling for the execution of Christian Cooper. Separated by 12 hours and hundreds of miles, George Floyd was murdered, and irrevocably changed the course of America. After responding to the scene in Minneapolis, Derek Chauvin unapologetically plunged his knee in George Floyd’s neck for nearly nine minutes. In the recording of the altercation, Floyd whimpers for his life as a pool of blood rushes from his nose. He chillingly repeats a phrase we were already familiar with, “I can’t breathe.” In response, Chauvin increases his grip. George Floyd’s last words were “I am about to die.” Chauvin kept his knee in the same position for nearly 3 minutes as Floyd lay, handcuffed, and unresponsive.

Photo courtesy of Adam Sherberg

The reality of being Black in America means fighting for the right to breathe. This country was born from Black hands and pillaged by white ones. The only crime our ancestors committed was stepping into the sun and not getting burned. To discuss race in America is to understand the theory of race is a byproduct of white supremacy, which fostered and established inferiority between the varying skin colors while denying the humanity of the darker-skinned. As a result, our systems were built on a foundation of oppression and wrongfully called progress. The response to George Floyd’s murder was a culmination of incidences that solidified the death of the American Dream. As Americans were dying and the highest unemployment levels were reached in light of Covid-19, billionaires tripled their wealth, and Jeff Bezos became slated to become the world’s first-ever trillionaire. Hospitals begged for the basic tools to try and fight for the survival of their patients. White protestors, primarily Trump supporters, protested social distancing rules meant to help this country survive. The rage I have carried every day since I turned thirteen soon churned around me as the United States crumbled under the weight of disillusionment.

Black pain has stretched across generations and destroyed communities. The Black spirit is broken, and so is this country. As the country continues to protest police brutality, police officers have incited violence and exposed the barren limbs of the very brutality being protested. Riots have sprung across the country, and are a culmination of circumstance and American history. In this time I have turned to words from James Baldwin and Toni Morrison because the plight of the black spirit has remained the same for the last 50 years. There has been an outpouring of support for George Floyd from all races. I realize now what changed. The way this country views George Floyd’s death is the way I have viewed the death of every unarmed Black person in America; without excuses, justifications, or questions of character.

I am proud of my generation for uniting in defiance of inequality, for finally taking a stand and saying enough is enough. I mourn all of the lives lost it took to get here; Trayvon Martin would have been twenty-five in February. We are now in the center of the flames, as the systems of oppression burn around us. From the ashes of despair, blooms hope for the future. I still carry rage, although it has reduced in size and relocated to the center of my chest. I wept again this week, in mourning and in relief. Then, I dried my eyes. There is still work to be done.